Legal Issues Of Cyber War Are Big & Complex

Much of the unchartered legal territory begins with questions of what it takes to trigger self-defense in cyberspace, and what does it mean for a nation-state to have 'effective control' of a hacker?

Claims that technical experts have solved attribution ignore legal challenges that could slow or limit how states might lawfully respond to a major cyberattack.

First, a country hit with a major cyberattack would face the novel challenge of persuading allies that the scale and effects of a cyberattack were grave enough to trigger a right to self-defense under the UN Charter. No simple task, given that the UN rules were drawn up seven decades ago by countries seeking to end the scourge of traditional, kinetic warfare. Jurists still debate how self-defense applies in cyberspace and US officials admit building a consensus could be a challenge.

If a victim state does corral a consensus that the right to use force in self-defense has been triggered, a second legal question could compound the attribution challenge even further.

Can the actions of a hacker be attributed to a nation-state as a matter of law? Answering this question presents a major legal hurdle if the attack is launched by an ostensibly non-state hacker with murky ties to an adversary government—a growing trend already seen in cyberattacks linked to Russia and Iran.

Legal precedents born out of traditional conflicts and proxy wars suggest the evidentiary burden to attribute the actions of non-state hackers to a state will be substantial. And experiences from recent incidents offer a discouraging preview. It took less than 24 hours for a prominent cybersecurity expert to cast doubt on claims by unnamed US officials that China was behind the breach of OPM’s networks. Official accounts of Pyongyang’s role in the Sony attack played out similarly, with news outlets featuring competing expert accounts of responsibility—a line-up of suspects that included North Koreans, Russians, hacktivists, cyber criminals, and disgruntled employees.

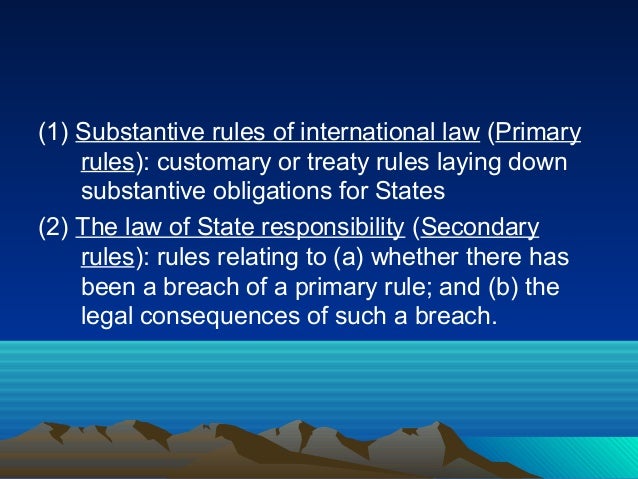

In 2013, some of the world’s major cyber powers reached a consensus that law applies in cyberspace, including principles of the law of state responsibility. Attributing conduct to a nation-state under this body of customary international law, however, requires extensive evidence of state control over a hacker—a significant ask of intelligence agencies already burdened with looking out for and mitigating the cyberattacks themselves.

Under the law of state responsibility, a state is accountable for the actions of individuals acting under its “effective control.” Legal scholars debate what “effective control” looks like in practice, but the International Court of Justice has ruled that violations of the law of armed conflict by private individuals can be attributed to a state only if it could be shown the state “directed or enforced” an operation. In a landmark 1986 case, evidence the United States financed, organized, trained, supplied, and equipped the Nicaraguan contras, as well as aided in the selection of targets and planning of contra operations, was not enough to show the United States exercised effective control over the contras. Contra war crimes, it followed, could not be attributed to the United States.

Extending the Nicaragua precedent to cyberspace, a victim of a cyberattack would likely have to prove more than an adversary supplied a cyber weapon to a non-state actor. A victim would instead have to show the state ordered or had “effective control” over all aspects of the cyberattack. Without such evidence, a victim’s lawful response options may be limited to actions against the non-state actors—cold comfort for a nation reeling from a cyberattack perpetrated by hackers financed, organized, trained, supplied, and equipped by a nation-state adversary. The victim state can of course decide for itself whether it has met the burden of proof in its attribution and unilaterally unleash an armed response—attribution, it has been said, is what states make of it—but a desire for international legitimacy could require meeting international law’s significant evidentiary burden before acting in self-defense.

Together, clearing these two legal thresholds will pose a significant challenge for countries seeking to respond to cyberattacks. Only after both are cleared is a victim endowed with a right to use force in self-defense against an attacker’s armed forces or other military objectives. This double burden could leave a victim state choosing between two bad outcomes: responding with force in a manner deemed illegitimate in the eyes of the international community; or responding with “non-forcible countermeasures” (criminal sanctions or diplomatic measures such as a demarche). Either outcome would lend support to the growing sense of cyberspace as a lawless frontier.

Expert contributors to the Tallinn Manual, an influential treatise on how international law applies to cyber warfare, are attempting to develop a consensus around how the law of state responsibility applies to the use of proxies in cyber operations. But until a shared understanding of state responsibility in cyberspace emerges, governments must themselves push for and enforce—as publicly as possible to ensure their behavior sets responsible precedents—a standard that punishes the use of proxies for cyberattacks and holds countries accountable for the consequences of those attacks. Public attributions, declassification of relevant intelligence, and the responsible use of countermeasures will do far more than tribunals and legal scholars can to shape how we deal with attribution and responsibility in cyberspace.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of State or the US government.

DefenseOne: http://bit.ly/1gLlH42